In 2025, the British Empire is still alive and well–and here is why

The British Empire never ended –only changed shape. Despite decades of rhetoric about decolonization and decline, it continues to administer dozens of colonial outposts—from the Caribbean to Antarctic

The Anglofuturism Podcast recently made waves by calling for renewed British settlement in Antarctica—describing the Falkland Islands and South Georgia as imperial footholds for a new age. But while many treat such talk as visionary or provocative, I would argue it is simply a recognition of something that already exists: Britain still has an empire.

With the recent UK–Mauritius negotiations over the Chagos Islands, the old empire is once again on the negotiating table. And yet, while many frame this as a long-overdue post-colonial reckoning, they miss the wider truth: Britain’s empire never ended—and in some respects, it has quietly expanded.

As America flirts with Trumpian visions of restored greatness and muscular international dominance, a curious silence persists about Britain’s own imperial presence. Yet while Washington talks, London governs. From Ascension Island to Tristan da Cunha to Antarctica, the British Empire endures—not nostalgically, but administratively, territorially, and politically.

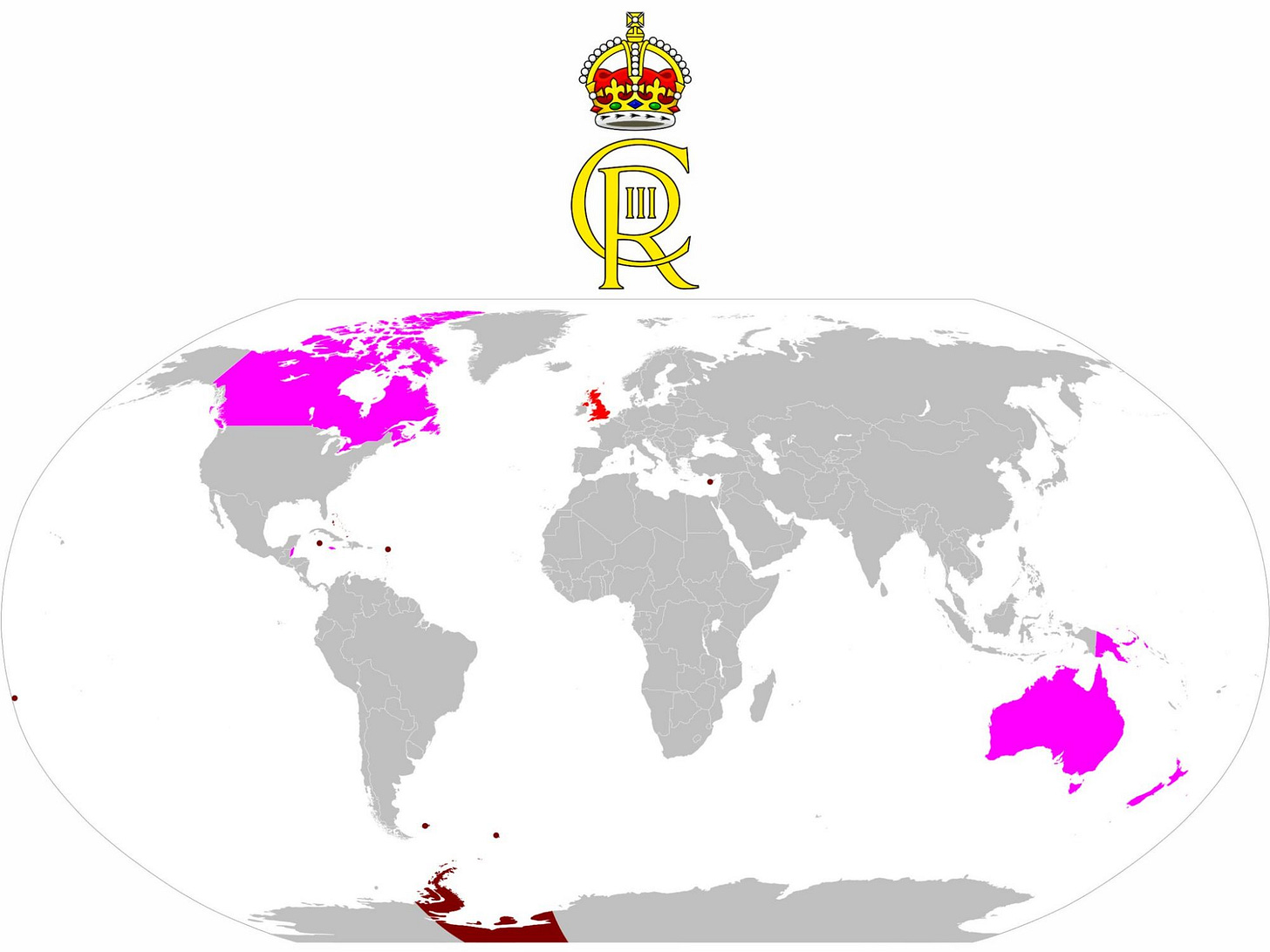

In 2022, as Queen Elizabeth II passed from this world, journalists solemnly declared the end of the empire. But they were two generations too late. In truth, the empire never ended. In her reign, it expanded southward into Antarctica, reasserted control in the South Atlantic, and continues to govern no fewer than fourteen overseas territories. The Crown may have ceased to call itself imperial—but its map still is.

II. The Empire That Refuses to Die: Evidence and Examples

“We are still an empire—because we never ceased to be one.”

The gloating of Christophobic postmodernists about the supposed death of the British Empire is not merely tasteless—it is factually false.

According to the very definitions used by historians, post-colonial theorists, and legal scholars, a state that exercises sovereignty over one or more overseas territories qualifies as an imperial polity. It does not matter whether the territory is large or small, populated or barren, rich or poor, insular or continental. The core fact is this: Britain rules territory beyond its mainland. And that, by any reasonable standard, constitutes empire.

---

A. Britain’s Living Colonial Holdings

The United Kingdom presently holds sovereignty over 14 overseas territories, commonly referred to by the acronym BOTs (British Overseas Territories). These include:

In the Caribbean: Anguilla, Montserrat, British Virgin Islands, Cayman Islands, and the Turks and Caicos Islands.

In the Atlantic: Bermuda, St. Helena, Ascension Island, and Tristan da Cunha.

In the Indian Ocean: the British Indian Ocean Territory (BIOT).

In the Pacific: the Pitcairn Islands.

Tory MP Andrew Rosindell has also suggested making Norfolk Island British again, because the residents prefer Britain to Australoa as an overlord and feel first and foremost British rather than Australian.

In the Southern Ocean: the Falkland Islands, South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands, and the British Antarctic Territory.

Jeremy Black, in his 2005 article “A Post-Imperial Power?” for the Foreign Policy Research Institute, rightly observed that Britain in the 21st century retains more territory than it held in 1500—a fact that no “decline-of-empire” theorist can erase. Some territories, like Bermuda and Gibraltar, have even rejected independence via referendum, choosing continued loyalty to the Crown.

James Brocklesby’s 2020 doctoral thesis Imperialism After Decolonisation reinforces this, noting that the governance of the Falklands, BIOT, and Brunei reflects a deliberate continuation of imperial authority, not a residual quirk of diplomacy.

Klaus Dodds, in his seminal 2002 work Pink Ice: Britain and the South Atlantic Empire, calls the southern territories exactly what they are: a South Atlantic Empire, complete with military bases, administered fisheries, mineral rights, and political projection—particularly through Antarctic presence.

---

B. Empire in Public Life and Political Language

The word empire is not merely an abstraction of historians. It lives still in the mouths of politicians, scholars, and citizens:

During the 2013 Falkland Islands status referendum, University of Leeds lecturer Victoria Honeyman told International Business Times that the islanders “passionately want to remain part of the British Empire.” The IBT headline itself read: “The Sun Still Never Sets on the British Empire.”

The Order of the British Empire (OBE) remains one of the kingdom’s highest state honours, conferred by the monarch annually. It is not the “Order of the Former Commonwealth” or “Order of the Post-Imperial Friendship”—it is the Order of Empire, and it thrives.

Imperial College London, one of the nation’s leading universities, proudly retains its name and identity, embedded in the memory of Britain’s global civilizing mission.

The British Commonwealth, now commonly called the Commonwealth of Nations, originated as an imperial structure. The monarch still serves as its symbolic head, and the member states are united by imperial genealogy, whether monarchic or republican.

British monarchy remains the imperial head of the Commonwealth of Nations.

Even Northern Ireland, one of the United Kingdom’s four constituent countries, is historically a plantation colony—a fact known well to Tudor and Stuart administrators who saw Ireland as the laboratory for empire. What worked in Ulster, they believed, could work in Virginia, Barbados, or Bengal. And it did.

---

C. Historical Continuity of the Imperial Title

From a legalistic and symbolic standpoint, the imperial concept has never been severed:

From 1876 to 1947, the British monarch bore the title Empress/Emperor of India (Indiae Imperator/Imperatrix).

Though India is now independent, the notion of a British Emperor has historical precedent far older than Victoria. Anglo-Saxon kings were styled in documents as Imperator totius Britanniae—“Emperor of all Britain.”

Blessed Bede’s 7th-century contemporary, Adomnán of Iona, described King Oswald of Northumbria as totius Britanniae Imperator a Deo ordinatus—“Emperor of all Britain, ordained by God.”

King Edgar was styled totius Albionis Imperator Augustus, and rex atque imperator—king and emperor.

In fact, King George III was considered for the title “Emperor of the British Isles” during the Acts of Union. It was never formally adopted, but the concept never vanished. And there is no legal, constitutional, or theological barrier to King Charles III reviving the imperial dignity as Emperor of the British Isles.

---

D. Modern Scholars Confirm: Empire Endures

This is not eccentric speculation. The scholarly consensus—though grudging in some quarters—is clear:

Jeremy Black: “Britain has an empire that is still far larger in extent than its overseas possessions had been in 1500.”

Klaus Dodds & Alan Hemmings: In their paper on Britain’s Antarctic geopolitics, they describe BAT and South Georgia as living imperial domains that extend Britain’s reach into polar affairs.

Denis Judd, in The Empire: British Imperialism from the 18th Century to the Present, writes that the empire’s transformation did not mean dissolution—and that Antarctic colonization may be its next chapter.

John Bowle, in The Imperial Achievement (1975), writes that “the Empire was not merely history. It was unfinished architecture—awaiting its southern wing.”

Even the 1992 study Britain's dependent territories: a fistful of islands by George Dowder described the BOTs as forming a “permanent empire”—a mix of inhabited and uninhabited territories that remain under full British sovereignty.

---

The Crown’s authority does not rest on whether academics believe in it. It rests on maps, on names, on treaties, and on the will of those who still fly the flag in wind-blasted outposts across the seas.

The empire is not dead. It has simply become more discreet, more polar, more maritime—and perhaps, more spiritual.

The flag still flies. The oaths are still sworn. The Crown still governs.

The British Empire has outlived its obituary.

E. The Falklands War: A War for Empire

The 1982 Falklands War was not merely about “self-determination” or a few windswept rocks in the South Atlantic. It was—by the admission of its own actors—a war for the empire.

Viscount Cranborne (later Lord Salisbury) said plainly: “This is not only about the Kelpers. This is about the empire, still.”

Newsweek’s iconic April 1982 cover bore the headline: “The Empire Strikes Back”, beneath an image of a British warship bound south.

In Iron Britannia (1983), a pamphlet by Anthony Barnett, it was argued that the war was in large part about Antarctica—about Britain’s access to South Atlantic oil, Antarctic krill, polar fishing rights, and the broader legitimacy of her claim to the British Antarctic Territory.

Edward du Cann, MP, in April 1982, spoke of the Falklands as containing “substantial treasures”—a statement revealing that material and imperial value were deeply entangled (Barnett 1983, 82).

During the conflict, Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher referred to the soldiers as “our boys”, portraying the conflict as Britain defending a purer, more morally intact version of itself—far from Brussels, and far from decline.

The Falklands, wrote one Victorian magazine, were “Antarctic New Britain”. And in 2025, Aris Roussinos—writing for UnHerd—called them a “new Highland Britain”, a remote bastion where young visionaries might build a future Britain untouched by urban decay and postmodern politics.

---

F. Empire as Historic Identity

Empire is not just a structure—it is a style, a psychology, a civilizational role:

From 1876–1947, the British monarch was styled Empress/Emperor of India.

Anglo-Saxon kings, centuries earlier, bore the titles Imperator totius Britanniae and rex atque imperator.

Charles III, should he desire it, could be rightfully styled Emperor of the British Isles.

Even without that title, the functions remain. The sovereignty is intact. The colonies exist. The laws apply. The Crown reigns.

Britain is not a post-imperial power. It is a transfigured imperial power.

The South Atlantic is not a relic. It is a frontier.

And the Empire never died. It merely boarded a ship and sailed south.

If you enjoyed this—comment your thoughts, share with a friend, or subscribe for future dispatches. I read every reply.