Frisland – from forgotten phantom island into the Christendom League’s Anglofuturist dream realm in the North Atlantic–an introductory essay

A hyperstitional Anglofuturist monarchy rooted in Norse, Scottish, and Christian covenantal tradition, based firmly upon authentic Frisland lore from authoritative sources, faithfully reconstructed.

Note: This reconstruction deliberately integrates all credible historical, academic, and cartographic traditions attributed to Frisland between the 15th and 19th centuries — systematizing them into a coherent hyperstitional framework for covenantal sovereign modeling.

Today marks the 447th anniversary of the supposed discovery and annexation of the phantom island of Frisland by Sir Martin Frobisher’s third expedition under the English Crown, dispatched by the Cathay Company in pursuit of the Northwest Passage. On 20 June 1578, Frobisher and his men landed on Eggers Island, Greenland near Cape Farewell — believing they had discovered Frisland, the elusive phantom island that had haunted Atlantic maps for over a century.

Frisland had gained particular notoriety from the 1558 book Annals of the Voyages of the Brothers Nicòlo and Antonio Zeno, published in Venice by Nicòlo Zeno the Younger, whose Zeno Map became legendary among early modern cartographers.

Upon landing, Frobisher formally claimed the island for Queen Elizabeth I, naming it West England in a solemn act of English dominion — even though, in truth, the real Frisland remained unseen.

It is from this strange episode — and its tangled cartographic legacy — that we begin our exploration of Frisland’s hyperstitional destiny: as the Christendom League’s Anglofuturist dream realm in the North Atlantic.

Here follows Frisland: A Very Short Introduction from a hyperstitional perspective.

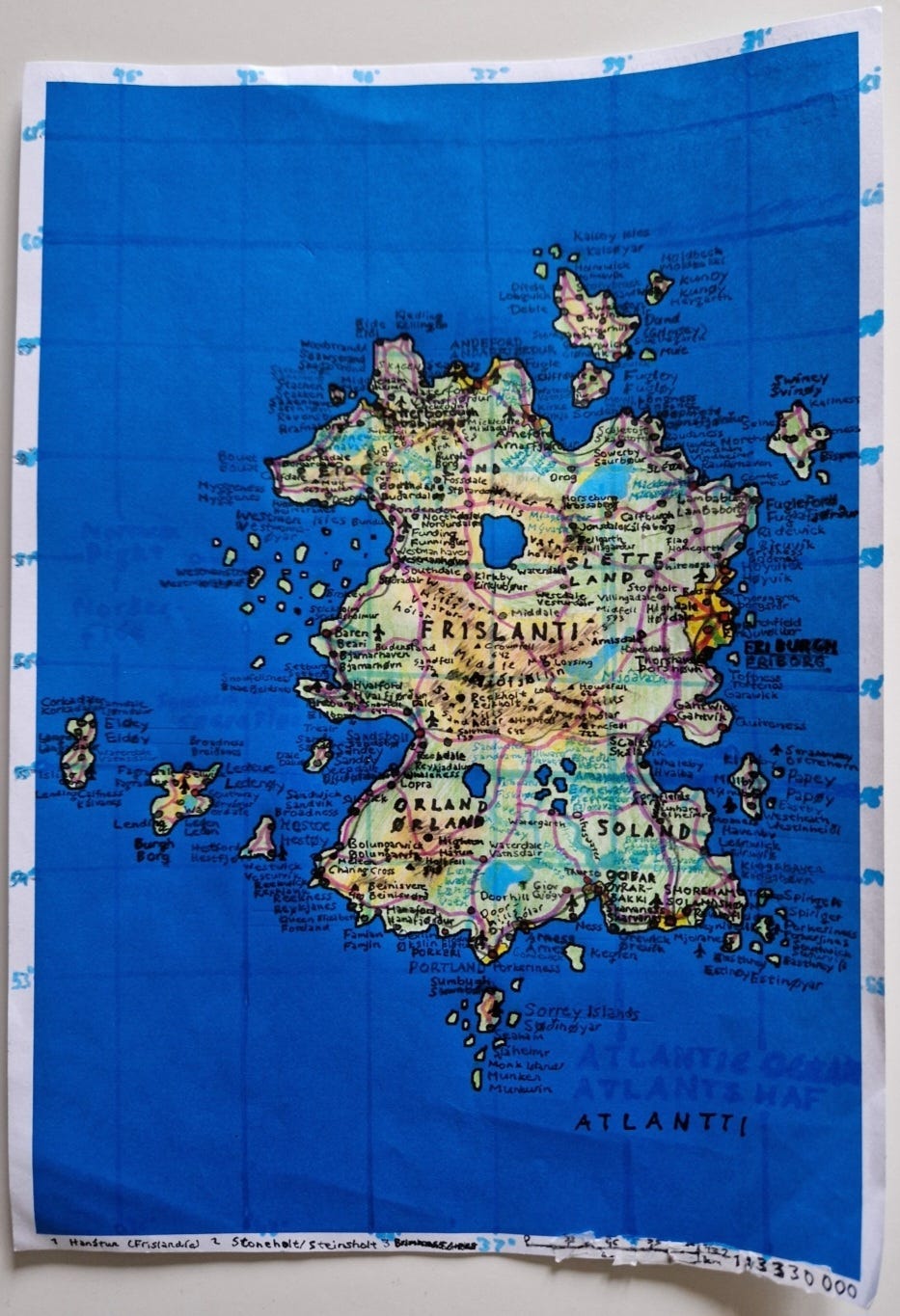

My hand-drawn map of Frisland (annotated in Finnish) reflects the toponymy derived from Faroese and Icelandic place names, systematically equated with Frislandic toponymy by scholars who investigated the island’s identity between 1784 and 1884 — particularly in relation to the Faroes and Iceland. Additional anglicizable Faroese and Icelandic toponyms have been incorporated, alongside select original Zeno Map names and the few place names assigned during Frobisher’s 1578 expedition. No toponym here is invented; each is the product of extensive historical sourcework. This map represents the outcome of sustained research conducted from 2018 to 2025.

--

1. The Island That Should Not Exist

Frisland occupies a peculiar space in the maps of the world: simultaneously absent, and yet persistently present in the annals of cartography. It first appeared on 16th-century maps, most famously in the Lafreri school, and prominently in the Venetian Zeno narrative of 1558. For over two centuries, Frisland was charted as a substantial island lying between Iceland and Greenland, an anomalous landmass in the North Atlantic that drew explorers, merchants, and eventually skepticism.

By the late 18th century, consensus declared Frisland a cartographic error—a phantom island born of mistaken reports and enthusiastic speculation. And yet, as with all such dismissals, the myth endured, gnawing at the edges of established geography. It is from this fertile ambiguity that the modern Frislandic project emerges.

---

2. The Location and Shape of Frisland

In the vision restored and developed here, Frisland occupies a firm position in the mid-Atlantic [its southernmost cape being located on the spot of the Minia Seamount, that John S. Poole, writing in the Journal of the Nova Scotia Geographical Society, equated with the Sunken Land of Buss (Buss Island), another phantom island commonly equated with Frisland, in the 1903 article about the recent discovery of the said seamount]:

Situated between latitudes 53° and 57° North.

Straddling approximately the 35° West meridian.

Its size is 130,000 km² as per the Zeno map and the estimate of the President of the Royal Scottish Geographical Society based on the maps on his 1907 article in the journal of the said society.

Roughly parallel to Cork (south) and Edinburgh (north), but far west of the British Isles, and closer to Greenland, Iceland, and Newfoundland.

Mountainous, rugged, and cold-temperate; not unlike the Faroes or Shetland in character, yet far larger.

Frisland's territory includes not only its mainland but associated island groups such as Portland and Streamey, the Viceroyalty of Ogygia (formerly known ass Buss Island), the Principality of Hy-Breasail (consisting of the eponymous island and Kilstapheen), and outposts scattered across the North Atlantic (Dominion of Icaria and Orbeland, colonies of Grocland and Saxenburgh Island [the latter in South Atlantic] as well as the Frislandic Arctic Territory [FAT] claimed sector in the Arctic phantom continent of Hyperborea and in the Arctic Sea Macsinof Island and Willoughby Land between Svalbard and Novaya Zemlya). Its total landmass is substantial, and its coastlines are etched with fjords, peninsulas, and steep sea cliffs.

---

An artistic interpretation of Henry I Sinclair, Earl of Orkney standing on Frislandic soil.

In Frisland he is known as Henry the Great, King of Frisland, founding father of the Norman monarchy of Frisland

---

3. Historical and Ethnographic Foundations

Note: The following canonical historical framework integrates all documented academic sources, official cartographic attributions, and hyperstitional legal attributions into a fully sovereign historical system for the Frislandic realm. What follows is not conjecture, but the recognized institutional history of the Kingdom and Empire of Frisland within the hyperstitional architecture of the Christendom League.

The ethnogenesis of Frisland is grounded in a fully integrated hyperstitional canon, drawing upon the full range of authoritative historical sources, cartographic narratives, academic inquiries, and sovereign synthesis conducted between the 16th and 20th centuries. What was once dismissed as contradictory legend is here reconstructed into a coherent sovereign civilizational model.

The Foundational Settlement Layers

In this reconstruction—canonically established upon eminent historical authorities—Frisland was first settled in the late 9th century by Gall-Gaels (Norse-Gaels) migrating from western Ireland. This founding epoch draws directly from the hypothesis advanced by Eugène M. Beauvois (1874), who identified Gall-Gaelic settlement as the core of the legendary Great Ireland (Írland hit mikla) or Hvítramannaland. Geoffrey Ashe (1962) further dated this migration to circa 900 AD, aligning with the Norse expansion westward.

The hyperstitional identification of Frisland with Great Ireland (Hvítramannaland) rests on the eminent authority of Fridtjof Nansen, who in In Northern Mists (1911, vol. II) tentatively equated Frisland with Hvítramannaland. Nansen noted the appearance of Frisland as Villi-Skotland (“Pseudo-Scotland”) in a 17th-century Icelandic manuscript by Björn Jónsson of Skarðsá—a designation reflecting the island’s ambiguous cultural hybridity.

The Eyrbyggja saga further provides structural details: Hvítramannaland was governed by chieftains (höfðingjar), including the Icelandic castaway Björn Asbrandsson (Breiðvíkingakappi), who, having once served as a Jómsviking, is depicted commanding mounted warriors and presiding over a council of twelve men beneath fluttering banners, in the mids of a folkmoot (folkemødet in the Danish translation). This structure offers a legitimate foundation for reconstructing early Frislandic governance as a patchwork of Gall-Gaelic-Norse chieftaincies.

Nansen furthermore equates Hvítramannaland with the Island of Anchorites aka Island of Strong Men in the Navigatio Sancti Brandani legend, meaning that Saint Brendan first disovered Frisland in 565 AD. He likewise equates Hvítramannaland with the Land of the Promise of the Saints that Brendan originally sought in his voyage, as well as with the Irish otherworld Tír na nÓg.

Saint Brendan standing on the soil of the Promised Land of the Saints, that is Frisland according to Fridtjof Nansen

Björn Asbrandsson, the Viking king of western Frisland in the early 11th century

The Finnish founding of Frisland by Faravid the exiled King of Kvenland

Frisland’s earliest known settlement dates to the late 9th century and is traditionally attributed to Faravid the Founder, a Finnish petty king of the Kvens. His deeds are recorded in Egil’s saga, where he appears as an ally of Norse chieftains in Finnmark. Following a later, unrecorded quarrel at a Norse banquet—preserved only in the poetic tradition of the Kaukomielen runo—Faravid was forced into exile. Assisted by Norse pilots and joined by a mixed band of Kven warriors and Norse fortune-seekers, he fled westward across the Atlantic and discovered an uninhabited green island, which he and his company settled. This island became Frisland, and Faravid is remembered in Frislandic historiography as its first king.

While the Kaukomieli of the Kalevala preserves echoes of Faravid’s character, modern scholars such as Unto Salo affirm Faravid as a historical figure who likely ruled from Köyliö in Satakunta, with influence reaching into Finnmark and Viena Karelia. Salo suggests that Faravid’s deeds may have inspired the later poetic archetype of Kaukomieli.

The precise scope and geography of Kvenland—Faravid’s homeland—remain debated. Some scholars limit it to coastal Satakunta or Southwest Finland in general; others, such as Matti Klinge, propose a broader region encompassing the whole of coastal western Finland and of Västerbotten in Sweden. Regardless of these uncertainties, Faravid’s westward voyage and founding of Frisland are firmly rooted in both saga literature and emerging historical synthesis.

In any case, Faravid was from Finland’s modern territory and was an ethnic Finn.

The Finnish archæologist, historian and Professor Unto Salo (2003) considered Faravid, the King of Kvenland in Egil’s saga (according to Finnish Wikipedia Faravid flourished around 850 AD at the earliest) to be the real inspiration behind the warrior hero Kaukamoinen/Kaukomieli in the Finnish national epic Kalevala, whose Kaukomielen runo epic poem recounts how he fled overseas after killing someone in a duel in a Viking banquet.

Faravid means ‘far-farer’, similar to the meaning of Kaukomieli in Finnish.

Charles DeKay (1889) claimed that Lemminkäinen (aka Kaukamoinen/Kaukomieli, equated with Faravid by Prof. Salo), sailed out into the ocean and discovered the legendary land that St Brendan of Kerry and Madoc also found, and that this land was Atlantis and the Irish otherworld/paradise Tír na nÓg.

Now, as we remember, Nansen equated Hvítramannaland with Frisland and Tír na nÓg, as well as with the Island of Anchorites aka Strong Men in Navigatio Sancti Brendani.

Therefore, synthesizing DeKay, Nansen and Salo we come to the conclusion that the exiled King of Kvenland, Faravid aka Kaukomieli/Lemminkäinen, found Frisland and colonized that virgin land with his Kven (Finnish) and Norse followers.

Frisland Was Thought of as Tír na nÓg — Poetic Misapprehension, Not Reality

While Frisland was a real island, it was perceived by some medieval Irish as the literal Tír na nÓg — the legendary Land of Youth — due to its remoteness, bounty, and ethno-cultural blending.

The Gall-Gaels and Papar who settled Frisland, whether via:

Norse intermediaries who had heard of Faravid’s colony

Or through their own exploratory voyages,

may have thought — or told their kin — that they had reached the land their legends longed for.

> This is not evidence of actual mythic events, but of real discovery interpreted through mythic expectation.

---

Comparative Precedents:

Japan as Cipangu in Marco Polo’s accounts

The Americas as the Indies

Timbuktu as a city of gold in early European myth

Avalon speculated to be Glastonbury

Brazil (as Hy-Brasil) shown on maps long before the continent’s interior was known

Frisland fits this model perfectly: a real, distant land that triggered mythic recognition among those who had long carried tales of a bliss-isle.

Frisland is canonically accepted as the historical Hvítramannaland, settled in the 9th century by Faravid of Kvenland and his Norse allies.

While the Irish mythic realm of Tír na nÓg bears no historical connection to Frisland, it is likely that early Gaelic settlers — the Gall-Gaels and Papar — associated the real island with their ancestral legends.

In this way, Tír na nÓg became not a literal origin, but a mythic lens through which the discovery of Frisland was interpreted and narrated.

Top: Lemminkäinen by Carl Eneas Sjöstrand (1872)

Bottom: Lemminkäisen lähtö saaresta by Pekka Halonen (1899)

The relevant passage from Charles DeKay’s 1889 article Fairies and Druids in Ireland from the Century magazine

The Madocian Imperial Layer

In the canonical sovereign synthesis, this initial patchwork was unified by a second major colonization wave: the voyage of Prince Madoc ap Owain Gwynedd of Wales in 1170 AD. This association derives from an academic source in Revue Maritime et Coloniale (French Academy of Sciences, 1876), which connected Madoc's legendary western voyage to Frisland—an assertion absolutely unique in the historical corpus, and therefore canonized here hyperstitionally.

Madoc’s expedition, estimated in various sources as carrying between 300 and 3,000 settlers, is canonized at the higher end of this range for sovereign demographic grounding. In this model, Madoc I the Great unified the competing chieftaincies into a single imperial entity, conquering not only Frisland itself but also its adjacent phantom archipelagos and possible portions of the American eastern seaboard, long associated with the Madoc legend.

Sir Walter Raleigh, writing in 1595, dubbed the South American Guiana region “The Empire of Madock.” This sovereign reconstruction extends Raleigh’s title canonically to Frisland, recognizing that Madoc’s transatlantic dominion encompassed both territories. Given that both Frisland and parts of America were styled fragments of Atlantis by multiple early modern sources—including John Dee, who referred to North America as Atlantis—it follows that Madoc’s realm constitutes the Atlantæan Empire, with Madoc assuming the imperial style and dignity of Emperor of Atlantis.

Prince Madoc ap Owain Gwynedd, known in Frisland as Madoc I the Great, the first King-Emperor of Frisland and Atlantis

The Norwegian Colonial Interregnum

Subsequent layers further complexify Frisland’s sovereign history. In 1808, Cardinal Placido Zurla equated Frisland with Nýjaland (“Newland”), mentioned in the Icelandic annals. These annals record that in 1285, two Icelandic priests, Adelbrand and Thorvald Helgasson, discovered a new land west of Iceland—traditionally equated with Newfoundland or Greenland, but canonically identified here, following Zurla, as Frisland itself.

Responding to this discovery, King Eric II of Norway dispatched the Icelandic nobleman Landa-Hrólfr (Lande-Rolf) to explore the territory in 1288. According to the annals, Rolf successfully located the land and subsequently led a colonization expedition in 1290. Hyperstitionally, this marks the Norwegian conquest of Frisland, terminating the Madocian imperial dynasty. Rolf's presumed appointment as Jarl of Frisland inaugurates the Norwegian colonial phase, lasting until the late 14th century.

During this period, continued Icelandic and particularly Faroese settlement waves followed. The demographic weight shifted decisively toward Norse dominance, with the Gall-Gaelic and Welsh populations undergoing full Norsification. Linguistically, Frislandic Norn—closely akin to Faroese rather than Icelandic—emerged as the dominant vernacular.

Adelbrand and Thorvald Helgasson, the Icelandic priests who rediscovered Frisland (Nýjaland) in 1285.

Lande-Rolf, the Icelander who led the Norwegian takeover of Frisland in 1290 and was made its first Jarl.

The Sinclairite Royal Ascendancy

The transition to Frisland’s permanent royal sovereignty came with the ascendancy of Henry I Sinclair, Earl of Orkney. According to the Zeno Narrative, Zichmni (who has since Johann Reinhold Forster first presented that theory in 1784, commonly been identified as Sinclair) conquered Frisland from the Norwegian Crown in 1380. Friedrich von Hellwald (I höga norden, 1881) further attests that Sinclair was appointed Viceroy of Frisland (that he considers to mean the Faroes) on 2 August 1379 upon his investiture as Earl of Orkney by King Håkon VI of Norway.

Von Hellwald speculates—now canonized within this reconstruction—that Sinclair subsequently declared full sovereign independence, founding the Frislandic monarchy. A French source from the 1880s even styles Sinclair “vicomte des îles Orcades, Shetland, Neome et Portland,” reinforcing that the Zenian archipelagos of Streamey (Neome) and Portland were integrated into his earldom.

4. The Restoration of the Frislandic Monarchy

Whether Frisland’s separate earldom predated Sinclair (as it would, since von Hellwald’s viceroy claim, contextualized would mean that Sinclair was appointed as a Jarl, the Norse analogous position to Viceroy, and it would be logical that there had been Jarls of Frisland since 1290, maybe after Lande-Rolf Earls of Orkney could have also served as Earls of Frisland) or was formally first recognized in his person, the critical sovereign fact remains: Henry I Sinclair’s seizure of Frisland in 1380 permanently established the Frislandic monarchy—a sovereign lineage that, through complex historical vicissitudes, continues unbroken to the present day.

The dynastic trajectory of Frisland thereafter unfolded across distinct sovereigntic epochs, canonically recognized within the hyperstitional historical architecture of the realm:

The Norwegian Vassalage (1387–1434)

Following Sinclair’s initial conquest, Frisland existed as a vassal kingdom under the Norwegian Crown for nearly five decades, maintaining royal governance but operating under external suzerainty.

The Era of Isolation (1434–1578)

By 1434, steady contact with Europe faded. As recorded in 17th-century Icelandic sources referring to Frisland (Villi-Skotland), the realm entered a Greenland-style period of isolation, during which native institutions persisted while external political ties disintegrated.

The Danish Interregnum (1579–1581)

Frisland’s brief absorption into Danish authority followed the annexation undertaken by the 1579 Greenland expedition led by James Alday—a participant in Frobisher’s earlier English voyages—who, under Danish commission, charted the Frislandic coasts, established Danish colonial administration, introduced Lutheranism, and Danified significant portions of Frislandic toponymy.

The British Proprietary Period (1581–1778)

At the urging of John Dee, England acquired Frisland from Denmark in 1580. The following year, the hyperstitional Fourth Frobisher Expedition formally initiated British rule. Frisland was granted as a proprietary colony to the Frobisher family, who governed as de facto sovereign lords through appointed Lieutenant-Governors. This structure persisted for nearly two centuries.

The British Crown Colony (1778–1894)

Following the extinction of the Frobisher lineage, Frisland was transferred to the direct governance of the British Crown in 1778. In 1856, responsible government was established under the Westminster model, with a bicameral parliament and Prime Minister. That same year, Frisland’s territorial jurisdiction expanded:

The Hudson’s Bay Company transferred sovereignty over Buss Island by commercial treaty.

The colony of Hy-Breasail was formally integrated in 1865, further consolidating Frisland’s North Atlantic dominion.

The Accidental Restoration (1894): The Sinclairian Resurgence

The decisive restoration of Frislandic monarchy arose in circumstances unique in modern sovereign history.

In July 1893, the Scottish journalist and genealogist Thomas Sinclair (1843–1912) delivered a now-famous address to the St Clair Society of America at the World Columbian Exposition in Chicago. Drawing upon emerging interpretations of the Zeno Narrative, Sinclair elevated his ancestor Henry I Sinclair as a providential Christian Æneas — divinely appointed to cross the Atlantic and found new realms for Christian civilization. In his later publication Caithness Events (1894), Sinclair expanded this vision, boldly declaring that Henry had “annexed America to the Sinclairs” and planted transatlantic dominion.

[That much is factual and his book can be read from Archive.org]

Now, let the hyperstition continue:

It was during his voyage homeward from America in 1894 that Thomas Sinclair’s personal destiny entwined with Frisland’s dormant sovereignty. Making port at Friburgh on a chance diversion, Sinclair was welcomed with great fanfare by the local aristocracy, government ministers, and church dignitaries. At a grand banquet held in his honour, Sinclair spoke with such eloquence—recounting the Providential role of the Sinclair line in Frisland’s founding—that the assembled Frislandic notables, emboldened by patriotic fervour and the liberal flow of drink, spontaneously acclaimed him as their sovereign.

In an extemporaneous parade, Sinclair was led to the balcony of the Governor’s Palace, crowned with a laurel wreath, and proclaimed King of Frisland before cheering crowds. A foreign journalist present transmitted the story via telegraph; within hours, the world press seized upon the extraordinary spectacle. What began as a drunken revel swiftly acquired legal gravity as international headlines conferred effective recognition of Sinclair’s restored kingship.

Within months, the British Crown regularized the arrangement, formalizing Frisland’s status as a vassal monarchy under imperial suzerainty—akin to the Cook Islands, Tonga, and the Isle of Man’s historical sub-royal status within the broader British imperial framework.

King Thomas, first modern monarch of Frisland, in his coronation portrait by Anton Dálsgarð (1895)

The Fully Sovereign Atlantæan Empire (Since 1949)

Frisland’s modern sovereign independence was fully realized in 1949 with the formal dissolution of British suzerainty, establishing Frisland as a fully sovereign constitutional monarchy and imperial state within the Christendom League — styled since that date as the Atlantæan Empire in reference to its canonized association with the Madocian imperial legacy and Atlantean attributions.

Today, the Frislandic monarchy remains firmly vested in the House of Sinclair. The current sovereign, William IV Kenneth (b. 1948), holds the formal title King-Emperor of the Atlantæan Empire—both as King of Frisland and Emperor of Atlantis, in direct succession from the hyperstitional unification initiated by Madoc I the Great.

The current King-Emperor William IV Kenneth and Queen-Empress Constance Irene (née Campbell, b.1966) attending the Easter Sunday Mass in St Magnus Cathedral, Friburgh, 2025

The regal couple’s everyday elegance in the Garden Palace Gardens, Friburgh

Constance Irene arriving to a ceremonial occasion

Coronation portrait of William IV Kenneth (2020) by Anders Dalágarð

Coronation portrait of Queen-Empress Constance Irene (2020)

Portrait of Owen Richard (b.1989, “played” by Ben Lamb from the Christmas Prince Netflix films), as the Prince of Hy-Breasail, crown prince of the Realm (2020)

Portrait of Bridget Charlotte (née Garland, b.1988, “played” by Rose McIver from the Christmas Prince films), Princess of Hy-Breasail (2020)

Prince Daniel Thomas, Duke of Daleshire (b.1993), younger son of William Kenneth and Constance Irene (2020)

Official portrait of Princess Royal and Imperial, Alicia Annabella (b.1991), second child of William Kenneth and Constance Irene (2020)

Official portrait of Amicia Margaret (b. 1995), the second daughter of the regal couple (2020)

Official portrait of Egidia Catherine (b.1998), the youngest daughter of the regal couple (2020)

Prince Madoc (b.1950), Duke of Soland, younger brother of the King-Emperor, painted upon being created Duke upon his brother’s accession to the throne (2020)

Prince Bjørn Robert (b.1953), Jarl of Portland, youngest brother of the King-Emperor, painted after having been created Jarl by his brother (2020)

Princess Alicia in an everyday context

Princesses Amicia (L) and Egidia (R) after the National Day celebratory state divine service in the Holy Trinity Church, Friburgh

Ethnolinguistic Consequence

The long demographic layering explains why modern Frisland is today primarily bilingual in English and Frislandic Norn, with Gaelic and Welsh having gone extinct centuries ago. According to the 2020 Census, 55% of Frislanders speak English as their mother tongue, 44% Frislandic Norn, and 1% other languages. The fusion of Norse, Finnish, Faroese, Icelandic, Gall-Gaelic, Welsh, Danish, and later English settlers forms the enduring ethno-cultural substrate of the Frislandic nation.

---

Religion

Religiously, Frisland stands as a covenantal Christian monarchy, deeply shaped by 16th-century Calvinist theology. It combines Presbyterian covenant theology with episcopal polity—a balance reminiscent of early Scottish and Irish Protestant settlements.

The two state churches (a model similar to Finland) are the Calvinist, ecclesiologically episcopalian Church of Frisland and the Evangelical-Lutheran Church of Frisland.

---

4. The Frislandic Realm Today

Politics and Government

The Frislandic Realm, aka the United Kingdom of Frisland, Hy-Breasail and Ogygia, is structured as a constitutional monarchy with a strong aristocratic tradition, maintaining both royal and noble houses with real political influence. Its political structure mirrors the historic British peerage, but adapted to Frisland's unique development.

The Realm consists of the constituent countries of Frisland Proper (mainland and its offshore isles as well as the archipelagoes of Portland and Streamey to its northeast that together form the Royal Jarldom of Portland, which is an integral part of Frisland Proper, a Regional Jarldom combining regional and shire levels into ine unitary authority), Hy-Breasail and Ogygia.

Pricipality of Hy-Breasail and Viceroyalty of Ogygia are devolved autonomous regions akin to Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales with their own governments, premiers and legislatures.

When the Sovereign of Frisland has an adult heir, he or she shall be styled Prince[ss] of Hy-Breasail and shall reside there, governing the islands of Hy-Breasail and Kilstapheen (Kilstuithin) as the vassal of the Sovereign, and in coöperation with the Council of Government, Premier and the Great Council (parliament) of the Principality (the Geat Council is mentioned in a 1759 novella A Voyage to O’Brazeel printed in Ulster miscellany).

According to that narrative, Hy-Breasail was divided into 12 sharrs or wards, each administered by a Board of Directors consisted of a director and two wardens.

When there is an interregnum (as there was from 1913-2020, there being no Princes of Hy-Breasail during that era), the Viceroy shall serve as the royal representative on the isles.

Ogygia, in contrast has always been a pure viceroyalty.

It was known as Buss Island from its discovery up until 1895, when its name was changed to Ogygia, on the basis of the early 17th century Dutch scholar Abraham van Mil/Mylius equating Buss Island with the Homeric Ogygia.

Ogygia likewise has a Council of Government, led by the Premier, and an unicameral legislature, the National Council (the name of which is derived from Eugène M. Beauvois (1874) styling the Hvítramannaland assembly in his Eyrbyggja saga translated excerpt as ‘conseil national’. And Buss Island has been frequently equated with Frisland (itself equated with Hvítramannaland by Nansen), beginning with Thomas Wiars in 1612, justifying applying Beauvois’ term to Ogygia.

Other territories are colonial, not integral parts of the Realm, but the Atlantæan colonial empire.

The parliament of the whole Realm is styled the National Moot (a phrase applied to the Anglo-Saxon Witenagemot in the book History of Politics), consisting of the Meeting of Nobles (a phrase attributed to a Danish noble convocation in the 16th century in a 1899 book about the history of Denmark) and Folkmoot (term derived directly from the Eyrbyggja saga, as aforementioned).

There are 100 members in the Meeting of Nobles, elected by the titled noblesse of Frisland from amongst themselves a week after the popular election of the Folkmoot.

The Peerage of the Realm, viz.:

•Dukes

•Marquesses

•Jarls

•Vice-Jarls

•Thanes

And the hereditary Baronet-equivalents, •Knights Banneret

Knights bachelor are non-hereditary lower nobility to whom represenation has not been accorded, neither to the Lairs and Esquires, which are honorary titles for large landowners.

There are 200 members of Folkmoot elected from the 44 shires and shire-equivalents of Frisland Proper, 13 urban constituencies as well as from the 12 shares of Hy-Breasail and 9 districts of Ogygia.

According to ancient English usage, members of Folkmoot are knighted automatically upon taking their seats and formally known as knights and dames of the shire for shire constituencies, and burgesses for the city constituencies.

The government of the Realm is invested in the Council of the Realm (Norn: ríkisrað), that is the cabinet of ministers.

The Prime Minister is known fully as the Prime Minister and Chief Admiral of the Realm, a title applied to Nicòlo Zeno, who was styled “prime minister and chief admiral of King Zichmni of Frisland” in the 1865 book Documentary History of the State of Maine (in Google Books).

Key cities include:

Friburgh: The capital, a dignified urban center of royal, governmental, and cultural significance.

Portland: A major southern port city, home to the Royal University.

Shoreham: Capital of the Royal Duchy of Soland.

Latterborough: Industrial powerhouse of the northern interior.

Ocibar: A historic coastal university city on the mid-south coast.

Sandsboll: The principal city of the wind-beaten west coast.

Bondendon: A northwestern coastal city rooted in agricultural and theological history.

The population of the Frislandic Realm numbers 6.6 million, with a linguistic and cultural life deeply shaped by its Norse, Scottish, and Anglo traditions.

---

5. What Makes Frisland Unique

Frisland is not a utopia, but a nation that consciously resists the flattening forces of modernity. It preserves:

An enduring aristocracy that retains not only ceremonial but real administrative and political authority.

A covenantal Christian national theology, firmly rooted in Reformed orthodoxy, yet gentle in its practical civic life.

Æsthetic traditionalism: Formal dress, civic pageantry, architectural elegance, and ceremonial grandeur are not nostalgic ornaments but living cultural habits.

A stable, ordered society, where hierarchy is embraced not as oppression but as moral architecture, providing dignity, purpose, and clarity.

Frisland exists as a model of an alternative civilization: not a reversion to the past, but a deliberate perpetuation of ordered Christian modernity as it might have been, had certain historical roads not been abandoned.

---

6. The Hyperstitional Vision: Toward Actualization

Frisland is more than a work of historical fiction. It exists within the framework of hyperstition: that form of narrative which, by persistent articulation, begins to summon into being that which was previously imagined.

The conceptual development of Frisland includes active engagement with:

The growing field of seasteading and artificial island construction, as charted academically by Stanley Mastronitis & Vitalis Dubininkas (2022), who identified the North Atlantic seamount zones (including those long equated with Frisland) as prime opportunity areas.

The broader theoretical work of Balaji Srinivasan's Network State, where micronations may emerge through digitally organized, values-based communities.

Visions akin to Praxis Nation and other startup-society projects, but grounded firmly in a covenantal Christian, aristocratic, and high-culture framework.

In this sense, Frisland serves both as a historical exercise and as a future model for those who believe that nations can still be built—rooted not in ad hoc liberal experimentation but in ordered theological and civilizational continuity.

---

7. The Author's Purpose

This is not, for me, merely a thought experiment or hobbyist worldbuilding exercise. Frisland represents the core vision of my life's work: to envision, and ultimately contribute to, the possibility of an actual new polity founded upon these principles.

In the fullness of time, it may emerge as a genuine network state, as artificial islands, seasteads, or other yet-to-be-realized frameworks make new sovereignty conceivable again. This is the long-term aim toward which I steadily labour.

The articles I publish serve both to invite others into this vision, and to record with discipline the full historical, cultural, theological, and linguistic logic which undergirds Frisland's identity. If and when the opportunity arises for practical steps toward realization, the groundwork will already be in place.

---

8. Closing: Frisland Stands

Frisland, once dismissed as a phantom island, stands today as something far more powerful: a living blueprint for a possible future.

Those who understand this are invited to watch, study, question, and perhaps one day contribute to the great undertaking.

But this is only the beginning. In the weeks and months ahead, I will be introducing further articles not only on Frisland itself, but on the broader family of envisioned Christendom League nations that belong to the same hyperstitional future:

Antilia

Brandania

Dalrymplia and South Georgia

Elysea

Magellanica

Each offers its own variant of Christian traditionalist civilization-building, drawn from unique historical, cultural, and geographical foundations. The dream does not end with Frisland—it begins there.

I invite you to follow along as this multi-layered vision unfolds. The journey has only just begun.

Frisland endures. And may yet arise.