The Fourth Rome: A Christian empire born from the phantom island of Antilia

How a mediæval phantom island offers a template for a Latinophone, neo-Roman, Catholic integralist seasteading empire – desert islands of Selvagens and Porto Santo, Madeira are equated with Antilia

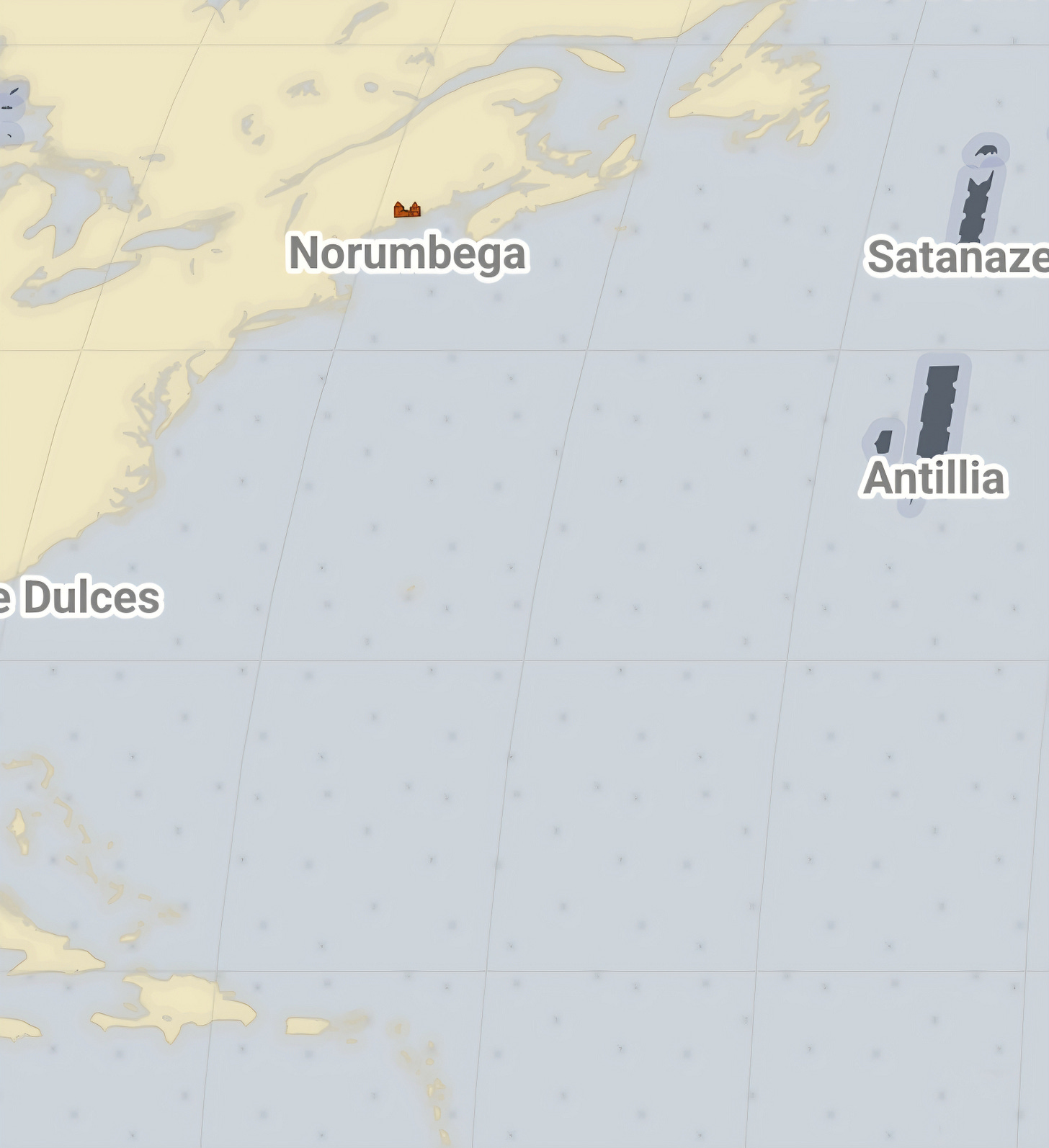

Antilia and Salvagia (Satanazes) depicted in the Map Myths website dedicated to cryptogeography (https://mapmyths.com/#antillia). Work of Henry Patton.

Imagined Visigothic flag design by an alternatehistory.com forum user, that is hyperstitionally the Antilian flag

Georgius Antonius, first modern King-Emperor of Antilia (“played” by James K. Hackett (1869-1926), who played King Rudolf of Ruritania in the first Prisoner of Zenda play (1897)–the bust’s face is his

---

I. The Legend of Antilia: Origins of the Seven Cities

In the shadowed cartography of the medieval Atlantic, one name emerges repeatedly: Antilia — the Isle of the Seven Cities. Among the most enduring of phantom islands, its story fuses legend, geography, theology, and hyperstition into a striking vision of civilizational resilience.

According to Iberian Catholic lore, in the year 714 AD — as the Islamic conquest overwhelmed Visigothic Hispania — seven Christian bishops, led by the Archbishop of Porto, gathered their parishioners and fled westward into the Atlantic. There, beyond the reach of the Moors, they discovered an unknown island. Burning their ships to sever all ties with the fallen homeland, they founded seven episcopal cities: Aira, Antuab, Ansalli, Ansesseli, Ansodi, Ansolli, and Con. Thus was born the Antilian Commonwealth, a Catholic theocratic polity of self-exiled Visigoths — a new Rome rising beyond the world’s western edge.

These legends, preserved in sources such as Martin Behaim’s 1492 Nuremberg Globe and Johannes Ruysch’s 1508 world map, would embed Antilia deeply within the Catholic geopolitical imagination for centuries to come. Behaim records the archbishop’s flight from Iberia; Ruysch details the ongoing episcopal rule of the Seven Cities. Galvão, Medina, and Columbus himself would all reference this remarkable western outpost.

Antilia became, quite literally, Ante-Insula — the island opposite Iberia.

---

II. Hyperstitional Imperial Evolution

Yet this vision of Antilia may not begin solely with the Seven Bishops of 714. Earlier narratives suggest that Antilia’s destiny reaches even deeper into antiquity.

According to classical sources such as Pseudo-Aristotle and Diodorus Siculus, Carthaginian seafarers discovered great Atlantic islands long before the Christian era. Some accounts suggest that the Phœnicians, wary of rival powers, forbade colonization of these new lands — preserving them as secret sanctuaries. Later still, around 80 BC, Roman records tell of Quintus Sertorius, the Lusitanian rebel commander, learning from Gadesian sailors of paradise islands two thousand kilometers west of Africa. While Sertorius never succeeded in establishing such a colony, the possibility that Roman noble exiles fled into the Atlantic remains a persistent conjecture.

In hyperstitional synthesis, we may envision Antilia as a Visigothic inheritor of both Iberian Romanitas and Phœnician-Carthaginian Atlantic knowledge — a Western Christian realm layered atop a substratum of prior exilic movements.

---

III. The Structure of the Holy Antilian Empire

Following the canonical narratives, Antilia developed into a fully theocratic Catholic polity, rooted in Visigothic ecclesiastical statecraft. Over time, it organized itself as a self-conscious Sacrum Imperium Antilianum — the Holy Empire of Antilia.

Its imperial structures reflect both late Roman and early mediæval Christian models:

Imperial Governance:

Concilium Imperii — Imperial Council (executive government)

Cancellarius Imperii — Imperial Chancellor (head of government)

Comitia Imperii — Imperial Congress (parliament), consisting of:

Senatus — Senate (nobility, clergy, and great patrician families)

Curia Popularis — Popular Assembly / Cortes (democratic representative lower chamber)

Ecclesiastical Authority:

The Archbishop-Primate of Antilia presides as Patriarchal Vicar.

Six suffragan bishops oversee the remaining historic cities.

Catholicism, in Latin Rite Tridentine form, remains constitutionally enshrined.

Law:

The ancient Visigothic Codex Euricianus, infused with elements of Mosaic Law, remains the civil legal foundation.

Capital:

Rodericopolis — named for Roderic, the last King of Visigothic Hispania, now restored in exile.

Provinces:

Seven provinces on Antilia proper, five on Salvagia.

Imperial Ceremony:

Emperors are crowned in Roman diadems, robed in purple, attended by lictors bearing fasces.

National Day features Romanized military parades with eagle standards, bump-helmeted cohorts, and adapted equestrian spectacles in the hippodrome.

---

IV. Distinction from Elysea (San Borondón)

While Antilia embodies the Visigothic-Roman Catholic legacy, its neighboring island cluster — San Borondón (Elysea) — reflects distinct Semitic threads.

Diodorus’ longer account describes an inhabited Atlantic paradise long known to Carthaginian-Phœnician seafarers. Some 20th-century scholars, such as Nahum Schoultz, speculated that Hebrew slaves brought westward by Phœnicians after the Assyrian conquest may have established lasting settlements, blending Hebrew and Canaanite elements. Over centuries, Elysea developed into a Hebræo-Punic hybrid culture with Carthaginian political features— ruled by kings, suffetes and councils, much like the ancient Senate of Carthage itself.

Thus Antilia and Elysea stand side by side — distinct yet entangled:

Antilia: Visigothic-Roman Catholic Empire

Elysea: Hebræo-Phœnician, Punic-Carthaginian microstate

---

V. The Portuguese Encounter & Colonial Integration (1487-1578)

In 1487, Portuguese navigators Fernão Dulmo (Ferdinand van Olmen) and Afonso de Estreito are said to have rediscovered Antilia. Unlike prior fleeting sightings, Dulmo successfully landed, annexing the archipelago to the Portuguese Crown. As capitão-mor (captain-general), Dulmo established Portugal’s initial administration.

While later Azorean and mainland Portuguese settlers added new layers to Antilia’s population, its governing structures remained firmly Romanized. Crucially, Latin — not Portuguese — persisted as the official language of law, state, and ceremony, maintaining continuity with Antilia’s original Visigothic-Roman character.

---

VI. Sebastianism: The Messianic Catholic Restoration Mythos

Central to Antilia’s mythopoetic rise is the uniquely Lusitanian phenomenon of Sebastianism.

After the death (or mysterious disappearance) of Portugal’s King Sebastião at the ill-fated 1578 Battle of Alcácer Quibir, widespread legends claimed he had fled across the Atlantic to Antilia, where he established a secretive Christian monarchy — the Hidden Kingdom.

Over generations, Sebastianist prophets imagined his descendants ruling this concealed realm, waiting for the providential hour to restore Christendom’s sovereignty.

These prophetic cycles — blending Catholic messianism, Marian devotion, and Iberian imperial longing — became foundational to Antilia’s identity.

–—

VII. Imperial Consolidation and Fonia: The Colonial Apex

By the late 19th century, Antilia sought to elevate its international status in the age of European empires.

In 1897, Antilian forces annexed the real-world West African polity of Fonia, historically located in present-day Senegal and Gambia — a genuine 17th–19th century empire recognized in European diplomatic records.

Modeling itself on European precedents — much like British monarchs styled themselves Emperors of India — the Antilian sovereign adopted the titles:

King and Emperor of Antilia

Emperor of Fonia

By these means, Antilia entered the age of formal imperial parity, having hitherto been a mere kingdom. However, following decolonization pressures, Fonia was relinquished in 1960. Today, Antilia retains Arguin island off Mauritania, styling it Mauretania Arguinensis province — but also a scattering of Atlantic and Indian Ocean phantom islands:

•Atlantic colonial possessions:

•Saint Matthew and New Saint Helena (Sanctus Matheus et Sancta Helena Nova)-capital Mateopolis

•Diego Alvarez (Didacus Alvarus) near Gough, no permanent population

•Indian Ocean

•Antilian Indian Ocean Territory (AIOT)

•Apaluria Atoll

•Baixo Ambar Bank

•Sanctus Roque Piz

-military base

•Juan de Lisboa and Romeiros Islands (Joannis de Lissabona) – capital Ioannopolis

---

VII. Modern Political Evolution (Note: Hyperstitional Scenarios)

Author’s Note:

The modern political developments presented below are purely hyperstitional constructs for civilizational modeling. They are not expressions of political advocacy.

In the 20th century, Antilia underwent turbulent internal shifts.

Repeated revolutionary insurgencies by the Tribunists, a Marxist movement plagued the nation since 1922, with parliamentary system alternating with military coups trying to stave off socialist takeover.

In 1963 and 1970 the Tribunists nearly succeeded, but in 1973 with Cuban and Soviet support they overthrew the monarchy and declared the Antilian People’s Republic.

However in 1986, underground rightist military factions organized under the Cohors Christiana Antiliana Imperialista (CCAI) — known as Cohortists — staged a coup d’état with American CIA and Magallanican FIS (Federal Intelligence Service) support.

A young officer, Major Sebastianus Ravellus (b. 1953), led the coup and was installed as the First Consul of the Christian Republic of Antilia.

In 1993 he organized a plebiscite about the restoration of the monarchy, which was favourable, and invited the pretender to Antilia to ascend to the throne.

However, the Cohortists did not relinquish power, but the regime continued under the restored monarchy with Ravellus being appointed as the Imperial Chancellor chairing the Imperial Council.

He retained leadership of the ruling Coohortist party as well, styled its Capitaneus, shortened Capo, colloiqually known as El Capo.

As of 2025, Ravellus remains firmly in power, grooming his son Octavianus as his successor.

This structure resembles various 20th-century prætorian models:

Symbolic monarch under a military-led Catholic nationalist regime

Corporatist state structures

Revivalist Romanitas æsthetics within ceremonial spectacle

Antilia’s distinct blend of Latin American caudillo dynamics and Romanized neofascist statecraft gives it a singular institutional profile — a self-conscious parody, yet deadly serious in its hyperstitional construction.

Antilia is like a Latin American banana empire with the kind of operetta æsthetics as depicted by Hergé in his fictional Latin American banana republic of San Theodoros.

---

VIII. Hyperstition as Political Theology

Antilia stands as one of the most fully developed hyperstitional Christian statecraft models in existence — rooted in real legendary canon, sustained through centuries of speculative development, and now fully integrated as an institutional hyperstitional scenario.

Its purpose is not escapist fiction.

Its value is not nostalgic kitsch.

Its merit lies in demonstrating how serious Christian civilizations could hypothetically emerge from even the most improbable historical premises.

In this sense, Antilia belongs within the wider Christendom League framework — alongside Frisland, Hy-Breasail, Magellanica, and the broader exploration of covenantal Christian hyperstates.

Whether as intellectual model or sovereign thought experiment, Antilia now stands—proud, eccentric, sovereign.

IX. The Canonical Distinction: Why Antilia Matters as a Hyperstitional Model

Not science fiction.

Not reactionary fantasy.

Not NRx meme statecraft.

Antilia represents a fully codified Catholic hyperstitional civilizational design grounded in:

Real historical maps (Pizzigani, 1424; Zeno, 1558; and others)

Documented Iberian Sebastianist prophecies (17th–18th century)

Authentic Roman, Visigothic, and Carthaginian fragments

Full sacramental integration with legitimate Catholic theology

---

X. Hyperstitional Logic: The Canonical Sovereignty of Antilia

This is hyperstitional statecraft in its highest form:

Phantom geography becomes cartographically viable via bathymetric analysis.

Mythopoetic history becomes legitimate constitutional lore.

Fictional religious exodus becomes fully plausible civilizational foundation.

Traditional Christian polity is revived with full institutional rigour.

---

XI. A Clarifying Note to Readers

This model is presented as a fully codified hyperstitional sovereignty scenario — a sovereign alternative for intellectual and institutional exploration.

I do not present Antilia as a literal political project I intend to enact myself.

However, it stands as a sovereign design framework that could, in principle, inform real-world sovereign startup ventures committed to serious Christian statecraft.

Antilia belongs firmly within the Christendom League Sovereignty Project — alongside Frisland, Magellanica, Elysea, and Brandania — each of which will receive fully developed canonical essays.

---

XII. The Invitation

To those serious about post-liberal Christian civilizational futures:

Study Antilia.

See how sovereign alternatives can be architected.

Understand how serious statecraft can emerge even from the mists of half-forgotten maps.

We are building sovereign blueprints — not to daydream, but to forge models for serious institutional futures.

The restoration of Christian sovereignty begins here.